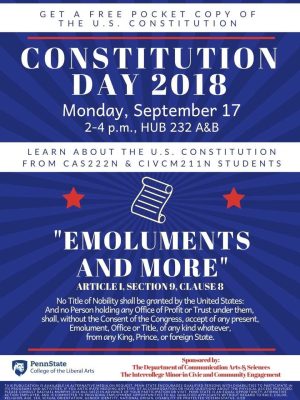

Tuesday, September 17th, 1:00pm – 4:00pm, HUB-Robeson Center, Heritage Hall

Learn more about the U.S. Constitution from CAS222N and CIVCM211N students, and CAS faculty!

Sponsored by The Department of Communication Arts and Sciences and The Center for Democratic Deliberation

“Emoluments and More” – Short essays on the U.S. Constitution

Below, read short essays by members of the Penn State community about a variety of Constitutional concepts, historical contexts, philosophical debates, and other topics related to the changeable and changing U.S. Constitution.

When Did Congress Last Declare War?

by Rosa Eberly

Associate Professor

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

Dept. of English

Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 of the U.S. Constitution grants to Congress the sole power to declare war. Do you know the last war declared after deliberation and voting by a constitutional act of Congress?

Were the current U.S. military actions in Syria or Yemen or Libya or Somalia or Niger declared by Congress? The ongoing wars in Afghanistan or Iraq: Were they declared by Congress? Was the Kosovo War in 1998 and 1999 declared by Congress? The Bosnian War, 1992-1995? Was the First Persian Gulf War of 1990 and 1991 declared by Congress? The 1989 invasion of Panama? The 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada? The Vietnam War? The Korean War?

The answer to all of those questions is no.

The last time the United States Congress met its constitutional mandate officially to declare war by deliberating and voting for the record to engage members of the U.S. military, each of whom takes an oath to protect and defend the U.S. Constitution, was 76 years ago, in 1942. That year the U.S. declared war on Rumania (correct spelling in 1942), Hungary, and Bulgaria. A year earlier the U.S. declared war on Japan, Germany, and Italy, days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii Territory. (Hawai’i became the 50th U.S. state in 1959.)

For a list of all 11 occasions on which the U.S. Congress officially declared war, visit the website of the U.S. Senate:

https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/history/h_multi_sections_and_teasers/WarDeclarationsbyCongress.htm

Meanwhile, the White House earlier this year acknowledged that the United States is currently at war in seven countries, the same number as during the last presidential administration (more information here https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/world/africa/niger-green-berets-isis-firefight-december.html and here https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/a3ywd5/white-house-acknowledges-the-us-is-at-war-in-seven-countries ). These actions are carried out by an all-volunteer military, part of the reason many Americans pay relatively little attention to the wars carried out in our name.

The Property Clause

by Denise Haunani Solomon

Head and Liberal Arts Professor

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

“The Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.” — Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2

The Property Clause has been getting attention in recent months as the current administration contemplates the future of national parks, forests, and monuments. An equally important question raised by the Property Clause is whether constitutional rights extend to territories, or “insular areas,” controlled by the United States. The answer to this question, based on Supreme Court decisions, is that Congress gets to decide which parts of the Constitution apply to which territories.

At present citizenship rights are extended to people born in 13 of the 14 US territories (the exception is American Samoa), but full protection under the Constitution is not guaranteed to these citizens. Historically, annexing territories has functioned to expand or protect the financial and security interests of the US – interests that have sometimes been at odds with conferring constitutional protections to inhabitants of insular areas.

A case in point is the history of my family in Hawaii. My great-grandmother was born in 1902, four years after Hawaii became a territory of the United States and 57 years before Hawaii became a state. She was born the grand-daughter of a Hawaiian kahuna – a wise man, healer, and leader in their community. By the time she was a teenager, my grandmother had two sons and worked for the Kohala Plantation on the big island of Hawaii. She had five more children, while continuing to work in the sugar cane fields of the Halawa Plantation. To make money, she boiled hot water for other members of her plantation camp, about 100 people in total, and hand washed clothes for other families.

My grandmother was part of a large population of Hawaiians and predominantly Asian immigrants who lived the hard life of indentured servants until statehood for Hawaii demanded better treatment of the labor force.

Sometimes the financial and security interests of the United States are at odds with conferring constitutional protections to inhabitants of insular areas.

The Migration or Importation–or Deportation–of Such Persons

by Anthony Irizarry

Doctoral Student and Graduate Instructor, Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

June 21, 1788: The U.S. Constitution is ratified when New Hampshire becomes the ninth and last required state to approve it. Tucked away in Article I of this document, a compromise can be identified.

Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 reads as follows:

“The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for Each Person.”

A compromise was struck in the name of unity between southern states and the infant nation. This compromise prevented federal interference in matters of the transatlantic slave trade for twenty uninterrupted years. In those twenty years, tens of thousands of Africans were imported into the fledgling nation.

Tens and tens of thousands. Compromise carries within it material consequences.

Fast forward 229 years.

May 7, 2017: Texas Senate Bill 4 is signed into law by Gov. Gregg Abbott. In that law, often called the “Sanctuary Cities Law,” rests another compromise between the states – Texas, in this case – and the federal government. The law mandates that local law enforcement cannot interfere with or hinder the progress of any federal investigation relating to immigration in the state of Texas.

The ethos of the law is similar to that of its federal predecessor, Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution. Yet the Texas Sanctuary Cities Law arguably blurs state and federal law. Using Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 as its point of departure, the Sanctuary Cities Law could very well read: “The Migration or Deportation of such Persons as the Federal State now existing shall think proper to admit or exclude, shall not be prohibited by the States.” Further, this Texas compromise does not have a twenty-year — or any — limit.

In the months since Texas Senate Bill 4 was signed into law, thousands of immigrant children have been separated and detained in Texas under federal orders — federal orders that cannot be disrupted by local or state law enforcement — federal orders that benefit from a compromise struck in the name of national unity.

Compromise once again carries within it material consequences.

Article Ø, Section Ø of the U.S. Constitution: The Right to Public Education

by Michael J. Steudeman

Assistant Professor

Director of CAS100, Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

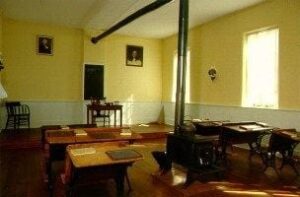

Among the elites who drafted or inspired the language of the Constitution, it was common to stress the importance of public education to the future of the republic. Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington all publicly argued for some form of publicly funded education. Though they were not at the Convention, influential figures like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams agreed on the importance of schooling to the republic. Adams was unequivocal: “There should not be a district of one mile square, without a school in it, not founded by a charitable individual, but maintained at the expense of the people themselves.” Their views were by no means idiosyncratic for the time. As the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia, legislators in New York guaranteed that “schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged” in the vast region encompassed by the Northwest Ordinance.

There seemed to be wide agreement that schools would be essential to the young nation. Yet the finished Constitution was mum on the topic, and judging from James Madison’s notes, its drafters barely even addressed it. The omission is strange, in part because the inclusion of educational language would have helped to galvanize the Founders’ own educational efforts. From Washington’s call for a National University to Jefferson’s (Madison-backed) proposal for a system of schools in Virginia, many of the Founders’ ambitious educational proposals failed. They likely would have been helped along by explicit constitutional language. Why didn’t they set themselves up for success by placing a guarantee to education in the Constitution?

In part, the absence of an educational guarantee reflected vast disagreements among the Founders about what “education” should do. Franklin’s proposed Academy, for instance, sought to promote economic mobility among the hard-working poor. Rush—the other Benjamin from Philadelphia—hoped a school system could cultivate “republican machines,” deferent citizens who could recognize and sustain a virtuous public. Washington’s envisioned university was intended to prepare a patrician elite for social leadership, whereas Jefferson endorsed a state common school system to discover the “natural aristocracy” scattered among the population. Widely agreed upon in principle, then, “education” was a conflicted concept in practice. Subsequent generations’ struggles over academic standards, students’ civil rights, and religious practices in the classroom attest to just how contentious an idea “education” can be.

Regardless of why the Founders left education out of the Constitution, many scholars, legal experts, and public education advocates argue that they made a grave mistake. Although every state affirms support for public education in its Constitution, states are inconsistent regarding how long students should attend, how schools will be funded, and what quality of learning students should receive. When students in failing state systems try to fight for improved learning conditions, an absence of constitutional language places them on shaky legal ground. For instance, in a case this year advanced by Michigan students, Federal District Judge Stephen J. Murphy concluded that states are not required to “affirmatively provide each child with a defined, minimum level of education by which the child can attain literacy.” In other words: there is no constitutional right to the resources someone needs to learn to read. In the face of decisions like Murphy’s, persistent funding disparities, and growing pressures on educators, a growing chorus aims to make the promise of education explicit in the Constitution.

For recent arguments on a Constitutional right to an education, see:

http://theconversation.com/the-constitutional-right-to-education-is-long-overdue-88445

The Distance Between the Nineteenth Amendment and Us

by Rosa Eberly

Associate Professor, Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences and Dept. of English

Last month marked the 98th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment being quietly signed into law. From the National Archives: “Achieving this milestone required a lengthy and difficult struggle; victory took decades of agitation. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, woman suffrage supporters lectured, wrote, marched, lobbied, and practiced civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered radical change.”

I have long used the Nineteenth Amendment as a kind of historical measuring stick for assessing how and whether We The People are working to create a more perfect Union. My mother was born three months before ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. In the language I grew up with, 1920 was “the year The Women got The Vote.” Yet not all women embraced the opportunity to vote, and, indeed, not all women gained the right to vote from the Nineteenth Amendment. While the Nineteenth Amendment allowed white women to vote, it did not extend voting rights explicitly to people of color.

The roots of that exclusion inhere in the women’s rights movement itself. As Penn State Professor of History and Women’s Studies Lori Ginzberg told NPR in 2011, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who helped organize the world’s first women’s rights convention in 1848, thought of women’s rights as white women’s rights. “When (Stanton) said ‘women,’ … she primarily had in mind women much like herself: white, middle-class, culturally if not religiously protestant, propertied, well-educated.”

Getting the Nineteenth Amendment into law took decades of organizing, work, and civil disobedience. Again from the National Archives: “Between 1878, when the amendment was first introduced in Congress, and 1920, when it was ratified, champions of voting rights for women worked tirelessly, but their strategies varied. Some tried to pass suffrage acts in each state—nine western states adopted woman suffrage legislation by 1912. Others challenged male-only voting laws in the courts. More public tactics included parades, silent vigils, and hunger strikes. Supporters were heckled, jailed, and sometimes physically abused.”

Find more resources on the Nineteenth Amendment here https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/18/books/review/womans-hour-elaine-weiss.html and here “Colby Proclaims Women Suffrage” https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1920/08/27/issue.html

And Now, A Brief Word from Cicero

by Michele Kennerly

Assistant Professor, Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences and Dept. of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies

Though emolumentum launched into language in ancient Rome, it is not a frequently used word in classical Latin. (Transformed, it ends up in Old English in the fifteenth century after a journey through Old French.) What can we learn from its appearance in a famous rhetorical text?

“Gratissima autem laus eorum factorum habetur quae suscepta videntur a viris fortibus sine emolumento ac praemio […]”

“But the very most gratifying praise belongs to deeds that seem to have been undertaken by commanding men without profit or payment.”

Cicero, De Oratore 2.85.346

Cicero is known for his words but not for being brief. His prolixity results from his taking on complex questions about how to live a public life. In 55 BCE, while Julius Caesar amassed increasingly more military power, Cicero composed De Oratore (On the Orator), a lengthy work constructed like a dialogue and whose central preoccupation lies with establishing the qualities that make for a good orator, essentially, a spokesperson for res publica (literally, the public thing).

The excerpt above hails from a part of the conversation in which the élite men talk amongst themselves about speeches of praise and what virtues do the most potent public work. One of the category-sets of virtue they discuss distinguishes communal virtues (e.g., trustworthiness, kindness) from individual virtues (e.g., dignity). It is not long thereafter that the excerpted sentence appears. The use of the superlative form (“gratissima”/“most gratifying”) in the excerpt tells us there’s no controversy on the matter of what actions from what sort of people in what sort of conditions earn the praise most pleasing for a community to hear. A public person’s being appropriately motivated is something communities recognize as in their interest to know, and that has long been so. The “seems” (videntur) in the excerpt is noteworthy, and stereotypically Ciceronian: we usually cannot know, definitively, whether a public figure received “profit or payment” for their deeds, but we need to read the signs.