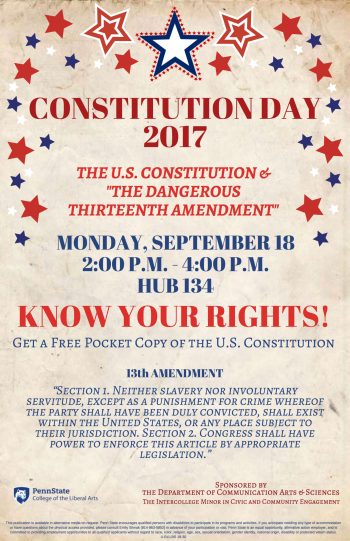

Tuesday, September 17th, 1:00pm – 4:00pm, HUB-Robeson Center, Heritage Hall

Learn more about the U.S. Constitution from CAS222N and CIVCM211N students, and CAS faculty!

Sponsored by The Department of Communication Arts and Sciences and The Center for Democratic Deliberation

Dreams of Union, Days of Conflict: Communicating Social Justice and Civil Rights Memory in the Age of Barack Obama

by Kirt Wilson

Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences, Penn State University

A Preliminary Note from Jeremy Cox, Assistant Director of CIVCM:

On November 11, 2016, at the Marriott Downtown in Philadelphia, Dr. Kirt Wilson delivered his Carroll C. Arnold Distinguished Lecture to a capacity crowd of communication scholars. Over the next forty-five minutes Dr. Wilson challenged his audience to consider contemporary perceptions of race relations between white and black American within the context of public memory of the civil rights movement. His speech was moving, evocative, and challenging—more so given the ambiguities of the political climate in which he spoke. Contra expert opinion and conventional wisdom, Donald Trump had just been elected the nation’s forty-fifth president, a fact not lost on those attendance. Mingled cries of shock and lamentation echoed through the hallways of the National Communication Association Convention no less than they did in cities and towns across the country.

I remember vividly that many in attendance hoped for a message that would make sense of—or even provide deliverance from—the anxieties of the present. Stephen Hartnett joked as much as he made his introductions, remarking sardonically, “Kirt Wilson is here to save your soul.” What Dr. Wilson offered instead was a sobering reminder that the fears of many in attendance were rooted as much in a willful forgetting of the past as they were current exigencies. It was, to me at least, a devastating performance of critical scholarship combined with an intensely humanistic attunement to the nation’s troubled history.

We are, Dr. Wilson contends, constrained in our understanding of race relations by our shared memories of the Civil Rights movement. As these events have undergone reinterpretation from “a social movement that once divided the country” into “an important part of the nation’s symbolic and material economies,” they have become, for better or worse, touchstones against which the nation’s racial progress is judged. The “success” of the civil rights movement has been transformed into an American story of triumph over adversity, now thankfully relegated to the past (where many would prefer such matters remain). Such a framework necessarily focuses on but part of the story, thus eliding uncomfortable truths about ongoing injustices.

In light of this year’s Constitution Day theme, we might consider how commonly held assumptions about the nation’s history with slavery similarly inform our oftentimes myopic views of race in America. How might the popular interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment as a “historical” document constrain our understanding of current systems of racial oppression and/or unfree labor? Dr. Wilson does not shy away from claiming, “slavery is not confined to the past; these conditions can and do continue.” Neither should we.

At this point, anything else I write will only delay from what you should be doing—reading Kirt Wilson’s brilliant, trenchant analysis of America’s ongoing struggle with its past. I therefore invite you to watch (or read) a truly important statement from one of the communication discipline’s most important voices.

To Watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtEBKqcdzOw

The “Slaughter-House Principle”

by Keren Wang

Ph.D. Candidate, Penn State University

The Constitution of the United States – Article XIII (Amendment 13 – Slavery and Involuntary Servitude)

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

It is sometimes tempting to overlook the Thirteenth Amendment as an anachronistic keepsake from the Reconstruction Era. It has been more than one hundred and fifty years since the Congress ratified Thirteenth Amendment. The abolition of slavery, once the most divisive issue haunting our nation, has since became saturated in our political and ethical worldview. The notion that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude… shall exist” had effectively became a sacred emblem not only for the United States, but also for the civilized world as we know it.

Paradoxically, the historical-thickness and totemic embeddedness of our Thirteenth Amendment is also what make this amendment feel forgettable. We are reminded of our constitutional tenets via explicit challenges (e.g. freedom of speech) and public debates (e.g. the right to bear Arms), and the issue of slavery and involuntary servitude just seem so settled in this day and age.

Or is it?

Many of the formal elements of race-based chattel slavery are no longer present, but what about the “underlying evils” of slavery? Consider, for example, the 1873 Supreme Court decision in the Slaughter-House Cases (83 U.S. 72). On the surface, the Slaughter-House Cases have nothing to do with slavery at all, as these cases mainly deal with economic conflicts between government-owned slaughterhouse operation and local slaughterhouses.1 However, the SCOTUS ruled in the Slaughter-House Cases that the Thirteenth Amendment indeed applies to a broad range of economically discriminatory actions. Justice John Archibald Campbell, who delivered the majority opinion of the Court, held the following interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment:

Undoubtedly while negro slavery alone was in the mind of the Congress which proposed the thirteenth article, it forbids any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter. …And so if other rights are assailed by the States which properly and necessarily fall within the protection of these articles, that protection will apply, though the party interested may not be of African descent. But what we do say, and what we wish to be understood is, that in any fair and just construction of any section or phrase of these amendments, it is necessary to look to the purpose which we have said was the pervading spirit of them all, the evil which they were designed to remedy, and the process of continued addition to the Constitution, until that purpose was supposed to be accomplished, as far as constitutional law can accomplish it.

The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S., at 72 (1873)

As evidenced by the above passage, even in the years shortly after its ratification, the SCOTUS has made clear that the Thirteenth Amendment offers broad protection against exploitative and discriminatory labor practices. The language of the Thirteenth Amendment never made “slavery” the exclusive signifier for race-based chattel slavery of the American south. In fact, Justice Campbell explicitly stated in the Slaughter-Case decision that practices such as “Mexican peonage” and “Chinese coolie labor system” were also slavery in terms of the injustices they effectively inflicted. Thus, the SCOTUS made clear in the Slaughter-House Case that the Thirteenth Amendment protects not only against historical forms of slavery, but also against emergent forms of discriminatory practices that share the “pervading spirit” of slavery.

What precisely is the “pervading spirit” and “evil” of slavery as the Court highlighted in the Slaughter-House Cases? To get something closer to a concrete answer to this question, we shall take a look at the 1968 landmark Supreme Court case Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (392 U.S. 409), where the SCOTUS held that:

“Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment rationally to determine what are the badges and the incidents of slavery … this Court recognized long ago that, whatever else they may have encompassed, the badges and incidents of slavery – its ‘burdens and disabilities’ – included restraints upon ‘those fundamental rights which are the essence of civil freedom.’ […] And when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery.”

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)

In Jones v. Alfred, the SCOTUS made an updated interpretation to the Thirteenth Amendment, effectively extending the “Slaughter-House principle” to include not only exploitative labor systems, but also other economic injustices that inherit the burdens and disabilities of slavery.

Hopefully, the judicial interpretations highlighted hereinabove could serve as timely reminders of an amendment that sometimes feels all too forgettable. The SCOTUS decisions also remind us that while the historical forms of slavery may no longer exist, their rhetorical and material overtones do sustain into our present conditions.

Notes

1 The disputes of the Slaughter-House Cases revolves around the effort by the New Orleans city government to create a government-owned meat processing plant, for the purpose of monopolizing all slaughterhouse operations of the city. The local slaughterhouses brought several suits against the city government, and these cases were eventually consolidated into one and brought before the SCOTUS.

The Thirteenth Amendment

by Mary E. Stuckey

Professor, Communication Arts and Sciences, Penn State University

I study the presidency and national identity, the unique ability the president has to speak for us as a nation, to give voice to the ideals that unite, and that also sometimes divide us. From the very beginning of the nation, many of those ideals have been inconsistent with our political practices. So a nation that was “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” was also a nation that held some people as property and enslaved them. Citizens with the courage to point out and work to resolve these contradictions are the ones who have helped bring the nation closer to its ideals; they are the ones who keep us reaching for the best we can be. And sometimes, their courage results in important changes in public policy.The thirteenth amendment represents one such change.

It wasn’t enough to ensure equality then, and it hasn’t led to equality now.The hard truth is that the Civil War was fought over slavery.The thirteenth amendment was the product of war.As we remember that war and its aftermath, we need to think long and hard about what we remember means for us as a nation.The recent events in Charlottesville and the presidential response to those events have made this a very important question. But he’s not the only one who has to answer it.

The question of slavery has been answered.The thirteenth amendment settled that issue for all time. But the question of the national commitment to human equality has not been settled.Q It is easy to offer cliches about how we are the freest, most equal nation on earth. Doing the hard work of equality is another matter. Our presidents have, for much of the last century, helped us see why that work is necessary, and have shown us how to do it.They have often been pushed to do so by citizens who have risked a great deal in their efforts to bring the nation closer to its own ideals.

What we are seeing now is, I think, evidence of how citizens force presidents to speak on issues of national concern, and in so doing, to define who we are as a nation.That so many people disagree so vehemently with the president on the question of who we are is unusual, to say the least, and marks this celebration of Constitution Day as one in which we decide the extent to which we are dedicated to the ideals and practices embodied in the amendments to the Constitution that followed the Civil War.

Women’s Advocacy against Slavery and the Changing Nature of Citizenship

by John Rountree

Graduate Assistant in Communication Arts and Sciences, Penn State University

As we mark this Constitution Day and specifically remember the Thirteenth Amendment, I am reminded of the decades of activism and political transformation that led up to the abolition of slavery in the United States. Many political communication scholars study “the public sphere,” which is a fancy term for the spaces of political activity where citizens debate political issues. To appreciate our nation’s history, it is important to understand how otherwise marginalized citizens have fought for inclusion in the public sphere throughout the years.

The buildup to the Thirteenth Amendment was such a time of contestation and transformation. In particular, women renegotiated their role in the public sphere starting in the 1830s, and this negotiation was most evident in female abolitionist movements. These women defied the norms relegating them to the domain of the household (the “private” sphere). Susan Zaeske has a wonderful book documenting the way that women during this time circulated anti-slavery petitions to Congress, and anyone at Penn State can access it through e-book on the library’s website! Women imprinted their “signatures of citizenship” on elaborately argued documents and laid claim to their First Amendment right to petition the government for a redress of grievances. Three million women’s signatures affixed anti-slavery petitions to Congress between 1831 and 1863. In an effort to silence the women abolitionists, the House of Representatives started passing “gag rules” in 1836 that did not allow the petitions to be discussed or considered. Rather than be discouraged, petitioners used it as a catalyst to get even more women to protest the injustice of slavery and to assert their rights as citizens in political spaces. Even though women nationwide did not achieve the right to vote until 1920, the abolition movement set an important precedent for women’s entry into the public sphere.

The Thirteenth Amendment in the Classroom

by Veena Raman

Lecturer in Communication Arts and Sciences, Penn State University

I teach an honors class for first year students. Currently, we are working on understanding how we learn about being good citizens and what we are asked to pay attention to or take action about.

As we discussed the US Constitution and what we know about this important document, it was interesting to note that few students knew about the Thirteenth Amendment. The best guess provided was ‘it had something to do with getting rid of slavery’. When asked, why we do not talk more about this Amendment, the answer was unanimous, “we don’t have slavery anymore, so we don’t have to talk about it.” It was time to examine the issue in depth.

An aspiring lawyer suggested we check if the courts have ever used this Amendment and cited it in their case law. As a class, we discovered that in addition to cases involving the Civil Rights Act, the Amendment was relevant to cases involving slave labor, and forcing someone to work for a creditor until a debt was paid.

This led to a discussion about instances where someone might be forced to work under threat of violence or coercion and we had a conversation about forced labor in sectors such as agriculture, construction, hotels, restaurants and domestic work. Students connected this to the issue of migrants who might not be in the US legally and how they might have no recourse to the legal system. We argued about the difference in being a part of a community and contributing actively to it, as opposed to being a citizen of a nation. We ended the class session with consensus that it was necessary to know how to help victims of labor trafficking and visiting the website of the National Human Trafficking Resource Center.

Pay or Stay: An American (not Dickensian) Practice

by Michele Kennerly

Assistant Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences, Penn State University

“Pay or stay” is the anodyne rhyme sometimes used to describe a practice whereby prison systems incarcerate people who cannot afford to pay fees and fines either they or family members have accrued due to a given corrective process (e.g., cops checking on the whereabouts of children who miss excessive school; a hearing; imprisonment itself). Articles documenting this practice often compare the cells that hold the indigent to a historical antecedent: debtors’ prison. Reference is commonly made to Dickens novels.

Notably, it was in 1842, the year before Dickens published Martin Chuzzlewit and A Christmas Carol, that Pennsylvania outlawed debtors’ prisons.

This year, then, marks 175 years since debtors’ prisons were outlawed in our Commonwealth. Yet they persist de facto if not de jure. And it is not deeper knowledge of Little Dorrit that will help us understand their persistence. Even to acknowledge that poverty is criminalized in the United States is not to arrive at full understanding, but it gets one closer.

For instance, three years ago, Eileen DiNino, a mother of seven children, from Reading, Pennsylvania, was sentenced to prison for two days to “pay off” $2000 in fines resultant from the process public schools initiate when a student misses lots of school. A day into her imprisonment, she was found unresponsive in her cell, and she died shortly thereafter. The prison had not treated her high blood pressure or responded to her calls for help in the night.

To more fuller understand “pay or stay,” one needs to situate it within the long history of the 13th Amendment. Its criminality exemption clause has allowed, again and again, the writers, enforcers, and interpreters of laws to justify deprivations of liberty that disproportionately affect people of color, since, disproportionately, people of color are targeted by police and economically disadvantaged.

Fact-finding underway by the ACLU of Pennsylvania turned up “thousands of cases each year in which Pennsylvanians are jailed for failure to pay court fine and costs. While the ACLU’s investigation is ongoing, it is clear that is many of these cases, the defendant could not have been jailed as punishment for the offense, but they are ending up in jail anyway when they cannot pay the fines and costs.”

Dickens coined lots of words, but not one of them suits this situation.

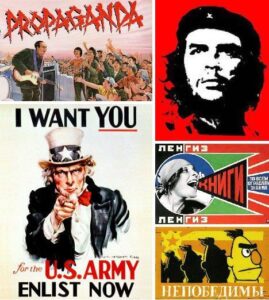

Persuasion, Propaganda, and the Thirteenth Amendment

by Lauren Camacci

Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow, Penn State University

This summer, I taught “Persuasion and Propaganda” to a group of newly admitted first-year students. This majority-white group of 18-year-olds was engaged and prepared, allowing us to have frank, in-depth conversations on topics like racism, nationalism, and toxic masculinity.

This group brought to my attention that some Amendments become warrants for students’ political arguments, where others are left by the wayside. Students routinely used the First Amendment as their warrant when arguing about, for example, flying the Confederate flag, while the Second Amendment played a central part in our discussions of polling as propaganda. In our discussions of racism in the United States, however, no student ever marshaled for their argument the relationship between the language of the Declaration, the Preamble, and the Thirteenth Amendment. The Bill of Rights certainly carries a particular authority, but it felt almost like this group of students simply forgot about the Thirteenth. This caused me to ask, what makes some Amendments memorable and others forgettable? Is it a matter of pithy phrasing? Or of identification?