Collective and Constitutive Memory

by Bradford Vivian

Associate Professor

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

I teach and conduct research in the rhetoric of collective memory, or how communities interpret, debate, and shape their understanding of the past in different modes of strategic communication. This process is often contentious; members of the public inevitably disagree on which stories from the past should be commemorated, why, and to what ends.

I regard much of current public dialogue about the Second Amendment, and its relation to the First Amendment, as an expression of competing public memories. The Constitution in general, as we discuss, admire, or critique it, involves the rhetoric of collective memory: a mythology surrounds it, and the document symbolizes, for many, a story of who we once were as a people and of how we came to be a freer, more perfect union in rejection of tyranny and outmoded forms of government. Hence the ongoing debates about whether the Constitution is a living document, the meaning of which changes for successive generations in response to ongoing and variously remembered events, or a static and essentially unchanging set of laws.

Contemporary debates over the meaning of the Second Amendment symbolize, perhaps most vividly, our collective inability to tell a harmonious story of rights, responsibilities, and the friction between individual freedoms and state authority—a story which would harmonize conflicting memories of the Constitution as a simultaneously evolving and static document. The distance between the First and Second Amendments seems especially poignant in our current era of gun violence awareness: the right to free expression and assembly and the right to own and use firearms in the United States currently exist in palpable tension. Horrors of gun violence beg the difficult question of when codified forms of speech turn into, or help justify, disturbing acts of violence or, conversely, the question of how one might counteract the anger and fear that leads to gun violence, and mitigate its traumatic effects, with words.

Members of the public habitually struggle with these questions by telling stories—stories of how our rights were won in the first place, of how their meaning has either changed or endured over the intervening centuries, and of the perceived historical goods and evils that such rights allowed, all in an effort to align those stories, despite the persistent social, political, and ethical tensions that they manifest, into a more perfect collective memory.

What Happens Between Messages

by Denise Solomon

Head and Liberal Arts Research Professor

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

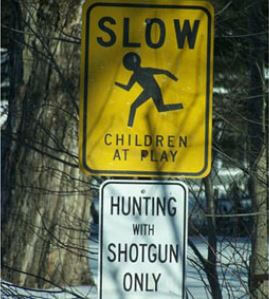

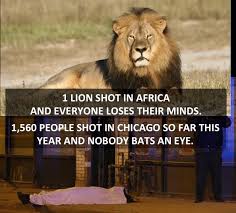

On the second day of CAS 203 I have for several years used this image to introduce the dynamics of interpersonal communication. The image has been an effective and often humorous way to make the point that, while communication involves overt messages, just as important is what happens between messages—in the inferences we make that tie overt messages together. Rhetoricians might call these inferences enthymemes. In any case, this semester, when I used the image again, I immediately regretted it.

So in the third class meeting I expanded on the point and added that the inferences we draw upon come, in part, from our collective conscious, from recent experience, and from culturally salient meaning. I admitted that I was unsettled by the slide in the previous class: In a year of so much gun violence, it wasn’t funny anymore. I apologized for not seeing that sooner. Students appreciated my apology, I think, and they also gained insight into how meanings change as a function of changes in our collective experience.

Occam’s Razor

by Harry Shearer

Guest Post

Sometimes, even in discussing supposedly Constitutional issues, Occam’s Razor is your friend. In all the back-and-forth about the meaning, value, and threat of certain states of the union flying the Confederate battle flag at official locations, one fact stubbornly remains unspoken: It is the loser’s flag. Losers don’t get to fly their flag, except in their garages. The war could be re-fought; the North has nukes.

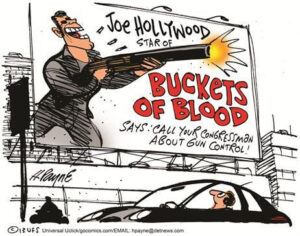

Similarly, although the presence of an estimated 300 million privately-owned guns in this country makes the issue of gun violence and control a political hornet’s nest, one simple fact stands out. Hollywood is the place where high-minded liberals campaign for gun control, asserting the legitimacy of limits on the Second Amendment, while relentlessly churning out more pornographic poetry of gun violence, relying on the relative limitlessness of the First Amendment.

Talking Through Differences

by Veena Raman

Lecturer

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

In my CAS 137 Rhetoric and Civic life class, we have started discussing the connections between ideology, identity, power and rhetoric. This image has been a powerful way for us to discuss how our values and assumptions guide us when we interpret what we see. We have been deliberating how we identify what is civic and the choices we make when we talk to others.

This week, it has been good to examine our right to speak about issues that interest us and what criteria we use to decide which issues to discuss, when, and with whom. With all the news media stories about gun violence, we are trying to understand why people have disagreements about gun rights and how to talk through our differences and find common ground. One of the questions the students posed to the class was, will we have a good discussion about any controversial topic if we knew, like in Texas, someone could be carrying a concealed gun and might use it if they got really angry? We are all trying to work out when we absolutely must speak up about an issue, what might be the consequences of speaking if something is too offensive to talk about, and how we can make decisions about these topics.

Between Academia and the Armed Forces

by Allison Niebauer

Ph.D. Candidate

Department of Communication Arts and Sciences

At the height of the Iraq War, my Dad deployed to the Anbar Province. I was a high school senior and though Dad had deployed before, it was one of the first times I was confronted with a seeming tension between supporting a defining characteristic of the Second Amendment—a “well-regulated militia”—and the freedom of speech guaranteed in the First Amendment. In an environment where my friends threw red paint on the local recruiters, while the sounds of mortar fire punctuated my infrequent phone calls with my Dad, I found a polarizing disjunction that many military families feel between a responsibility to uphold our freedoms, and the privilege of exercising them. This tension only grew after I joined the Air National Guard immediately following my freshman year of college, and eventually deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Trying to adjust to college life after deployment, I found myself alternating between extreme apathy and frustrated rage. The ideas generated in the classroom either seemed so esoteric as to hardly matter compared with the sharp reality of deployment, or vapidly convenient—arguments about the war, politics, and what it meant to be a citizen—without any skin in the game.

I was lucky to be among the roughly 50% of veterans who have used their GI Bill to go back to school, and graduated. To my surprise, I’ve ended up in the academy, oftentimes leading the discussions that I fear will seem out of touch, or worse yet—cheap—to the vets in my class. While acknowledging that everyone’s experience is different, I try to make my classroom a place where twenty-one-year-old me, fresh off deployment, would have wanted to be. I focus on application, attempting imperfectly to tie theoretical concepts to the immediacies of our shared life. I try hard not to let one political culture take over in the classroom, and ask everyone to support their arguments to the best of their ability—disagreeing with the ideas, but still respecting the experiences, of their classmates. I’m cognizant of the ways being out of the classroom during deployments can make it hard to return. I try to emulate my French professor, who, recognizing the signs of reintegration from her own experience as a missionary kid, invited me to her office, served me tea, asked me about my experiences, and thanked me for being a part of her class. I’m reminded that freedom of speech is a privilege best nurtured by a deep well of respect and civility.

For more information on the resources available to veterans at Penn State, visit the Office of Veterans Affairs. More information about the national program to help veterans with reintegration can be found at the Beyond the Yellow Ribbon website.

Weapons or Words: Which are More Dangerous?

by John Minbiole

Lecturer

Assistant Director of Graduate Studies

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

Weapons or words. Which are more dangerous?

In the Bill of Rights, speech, among other things, comes first. Guns second.

But should either be merely ranked one over the other? Should either be reduced to mere tools, or instruments? Rather, with a nod to Marshall McLuhan, should we view both as extensions of the human?

Shortly after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, Wayne LaPierre of the NRA brought to bear a hardy gun rights commonplace: “Look, a gun is a tool. The problem is the criminal.”

But is picking up a gun at all like picking up a hammer or a screwdriver? Does not a gun on one’s hands fundamentally change one’s entire worldview? To pick up a gun is to hold an uncanny power. From a distance and in a shockingly quick and almost effortless way, one has the capacity to end a life or many lives, ruin countless other lives, or even change the course of history.

Is the metaphor that LaPierre uses – inscribed in America’s collective memory in the 1953 film Shane – also simply a tool itself? Or is language also an uncanny power? McLuhan provocatively suggested that in an age of “electric technology,” language itself could be regarded as a weapon.

Do we sufficiently understand our relationship with either guns or language? Do we sufficiently comprehend either’s essence – not just their material existence as “instruments,” but also the uncanny extensions of human motives, emotions, reasons that both seem to offer?

Other thoughts and trivia:

– A gun is a tool, Gary Gutting says, but the question is: should we own one?

– Google search results for the exact phrase, “a gun is a tool”: 132,000.

– Google search results for the exact phrase, “a gun is not a tool”: 49.

– On the lighter side: are guns, like dildos, more a matter of one’s identity than of actual use?

– “Guns are basically that dildo sitting in a drawer. You own one—or a dozen—to own them. You can lie to yourself until you’re blue in the face, but the fact of the matter is they are closer to a knick-knack than a tool. Except they happen to be knick-knacks that can used to murder someone in your family during a dispute, to kill yourself in a moment of despair, or to go off accidentally and take a life or limb.”

– Amanda Marcotte, “Guns: So many people obsessing over a tool so few will ever use.” Raw Story.

On Safe Spaces

by J. Kurr

Ph.D. Candidate

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

The ability for LGBTQ folks, including myself, to find solace in a gay bar has its roots in the first amendment guaranteeing the right of the people peaceably to assemble. Following a 1966 “Sip-In” at Julius in New York City, the New York Court of Appeals struck down a New York State Liquor Authority rule that made it illegal to serve gay individuals. Since then, gay clubs have become places of refuge for LGBTQ folks, who have been cast out of their homes, workplaces, and places of worship.

On June 12, 2016, a shooter violated the sanctity of Pulse, a gay club in Orlando, Florida during pride month. The attack shook the LGBTQ community, and made many of us afraid to visit the one place we felt safe. Following the attack, gun-control advocates pushed for laws restricting individuals on the No Fly List from purchasing guns, and gun-right advocates pushed for LGBTQ individuals to arm themselves. Lost in this fallout is a simple truth: LGBTQ folks peaceably assemble in gay clubs to find safety, to create solidarity, and to disarm hate.

The “Sip-In” at Julius: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=91993823.

New York court case: http://reason.com/archives/2015/06/28/how-liquor-licenses-sparked-stonewall/1

Gay bars as “places of refuge”: https://web.archive.org/web/20191224231351/https://web.archive.org/web/20191224231351/https://www.thenation.com/article/please-dont-stop-the-music/

LGBT fear following Pulse: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/soloish/wp/2016/06/14/how-to-talk-to-a-queer-person-who-is-afraid-of-dying/?tid=a_inl

LGBT gun-right advocates: http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/06/the-gun-group-that-wants-to-arm-gay-america-213961

LGBT gun-control: http://www.cnn.com/2016/06/24/health/lgbt-gun-activism/

The Right to Bear Arms and the Confederate Flag

by Anne Kretsinger-Harries

Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof opened fire at Emanuel African Methodist

Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC, killing nine people. The shooting was a

hate crime purposefully inflicted upon the historically black church to

inflame racial tensions. Soon after the attack, a photo surfaced featuring

Roof holding a Confederate flag. The photo incited widespread national

debates over the Confederate flag and the subsequent removal of the flag

from prominent sites such as South Carolina statehouse grounds, Virginia

state license plates, and even the shelves of Walmart. Some people have

claimed that these recent debates over the Confederate flag detracted from

the more important issue at hand: systemic gun violence and the need for

reform. Proponents of flag removal efforts, in contrast, have argued that

the Confederate flag symbolizes and sanctions racial violence and white

supremacy.

http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/take-down-the-confederate-flag-now/396290/

http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/confederate-flag-debate-eclipses-one-gun-control

https://www.thetrace.org/2015/06/social-media-analytics-gun-rights-confederate-flag/

Do Violent Video Games Cause Violent Behavior?

by Jeremy David Johnson

Ph.D. Candidate

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

After the shootings at Columbine High School in 1999, news spread that the perpetrators, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, were avid video gamers. Their game of choice, Doom, was exceedingly violent, and was played by millions of other gamers. This discovery led to claims that video game violence spurred Harris and Klebold to act out their aggression with real weapons at their high school.

Since Columbine, possible connections between video games and violence have received perennial scrutiny. People question whether video games cause violence, whether they catalyze violent tendencies, or whether there is any link at all. Meanwhile, today’s games have become more realistic. With the growth of virtual reality, concerns that video games cultivate violent behavior will continue to be relevant.

Makers of video games tend to claim that their creations are artistic. They typically resist any notion that their games contribute to physical violence, including mass shootings. Still, they occasionally change their tone, such as when publishers offered “sensitivity” tweaks to their messaging at this year’s Electronic Entertainment Expo, set just days after the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/do-video-games-inspire-violent-behavior/

http://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/05/tieing-columbine-to-video-games/

“A Well Regulated Militia”? For What and for Whom?

by Anne Demo

Assistant Professor

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

One might not immediately think about immigration when considering the space between the First and Second Amendments. Beginning in 2004, however, a group of civilians began patrolling a 23-mile stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border to protest insufficient enforcement of the border. The right to carry handguns is legal in Arizona and protected by the Second Amendment. Still, leaders such as then-Governor Janet Napolitano addressed concerns that the rights to assemble and bear arms can cause problems from a law enforcement perspective: “People are entitled to exercise their First Amendment rights and entitled to assemble . . . . That’s why you can’t stop the Minutemen from coming even though, from a law enforcement perspective, it’s worrisome to have untrained people, potentially armed, performing what should be a law enforcement function” (Arizona Daily Sun 3/3/2005). In 2014, three different militia groups—the Oathkeepers, the Three Percenters, and the Patriots—began patrolling the border along Texas’s Rio Grand Valley, prompting similar concerns from a local sector of Customs and Border Protection.

Just as certain types of speech are said to fall outside First Amendment protections because of their harm, the question of safety posed at the intersection of the First and Second Amendments raises important questions. What (if any) types of arms might be deemed unprotected by the Second Amendment while exercising First Amendment rights to assemble? More broadly, what does the middle clause of the Second Amendment (italicized below) mean for law enforcement functions on the border and in other recent conflict zones such as Burn, Oregon?

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Public Speaking and Guns

by Adam Cody

Ph.D. Student

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

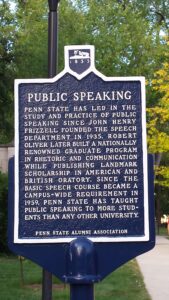

The Art of the Speaker, the textbook used for the public speaking class here at Penn State, opens with a story about the founder of the Speech department. At his initial meeting with his employers, John Henry Frizzell is warned that his predecessor “so feared for his life that he’d carried a pistol at all times” (Johnstone et al., p. 2). In the end, Frizzell’s patience and endurance win him the respect of trouble-making students and established faculty alike.

Glib and cutesy as it is, this story bases the tone for the communication class on the failure of communication. The textbook invites each student to be part of a great Penn State tradition: resenting the university’s oral communication requirement. And the historical students seek to silence the instructor through harassment and intimidation, not petition or even disputation. Frizzell, for his part, doesn’t attempt to solve his problem by talking to the students harassing him; he stoically ignores them until the students respect his “guts” (Johnstone et al., p. 3).

The tension of this early speech class is personified in the character whose absence drives this story: the gun-toting pre-Frizzell instructor. Lecturing on ethos with a firearm at his hip, the anonymous teacher occupies the shared space between the First Amendment and the Second. Speaking freely and bearing arms might both be possible solutions to a certain problem, and each flourishes in the absence of the other.

Written and Unwritten Constitutions

by Keren Wang

Ph.D. Candidate

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

A central focus of my research revolves around the distinction between written and unwritten constitutions. Written constitutions are formal legal documents creating and maintaining a self-referencing political entity for the legitimate expression of the sovereign will. Unwritten constitutions are socially embedded rule-frameworks governing social relations particular to a given society’s conditions and its intrinsic contradictions. The U.S. Constitution is a textually brief and rigid document. As the highest law of our vast and diverse land, it managed to endure for more than two hundred years with relatively few revisions (in comparison, the French Constitution underwent 17 major revisions since the end of the ancien régime). The remarkable stability of the U.S. Constitution is in part due to its limitedness. It is not meant to be an all-encompassing legal document governing all human transactions within our country. It does not seek to provide the absolute guiding principle regulating the private domain of the citizens, Rather, it is a political constitution for matters chiefly concerning the public sphere. Underneath our indivisible “One Nation,” there are unwritten constitutions that form collective beliefs and values and shape and regulate the human transactions at the communal level.

The Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, in my opinion, provides the key to understanding that political relationship. “We the People” implies that the United States is a republic grounded in popular sovereignty. The People as a singular noun implies the indivisibility and absoluteness of citizens understood in terms of their collective public capacity, not as “sovereign subjects” but as the sovereign in itself. However, the political “one-ness” of “we the people” does necessarily colonize or displace our heterogeneous private and communal lifeworlds. If we accept this basic separation between the public and private spheres, and between political and communal constitutions, it should be apparent that the U.S. Constitution (in its written form) at its core concerns the relationship between the sovereign and its citizens. From this interpretative angle, it should be evident that the Second Amendment should be interpreted in terms of its core political objective: citizens’ exclusive ownership of the state’s instruments of violence. Given the intrinsic limitations of the scope of our Constitution, the political goal of our right to bear arms must be considered separately from private and communal considerations.

There are divergent private sentiments and communal attitudes concerning the nature of firearms: whether we personally love or fear guns, and whether or not allowing or forbidding guns will make our community more or less safe. Those are important issues, of course, but perhaps they are considerations better to be decided on the ground at a communal level, and should not fall within the jurisdiction of our political (written) constitution. Being a popular sovereign republic implies there is no “Her Majesty’s Navy.” The central element of the right to bear arms as a political question has to do with our citizens’ power as the exclusive legitimate owner of the state’s instruments of violence, including the military and public security apparatus. Likewise, when understood in conjunction with the Preamble, the “well regulated militia” of the Second Amendment implies the citizen as both responsible for and beneficiary of the collective security of the republic. And the right to bear the state’s instrument of violence should not be unconditionally delegated to an abstracted governmental entity, for such an act is a surrender of absolute civilian leadership.

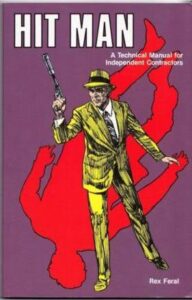

Hit Man: A Case Study in Incitement to Murder

by Brad Serber

Postdoctoral Scholar

Assistant Director, Intercollege Minor in Civic and Community Engagement

Dept. of Communication Arts and Sciences

In 1983, an author writing under the pseudonym Rex Feral published Hit Man: A Technical Manual for Independent Contractors with Paladin Press. The manual describes, among other things, detailed steps that one could follow in order to commit murder and get away with it. More specifically, parts of the manual describe how to make and use a silencer and how to dispose of weapons and bodies in order to make them hard to find and identify. Paladin Press sold about 13,000 copies of Hit Man. One of those copies ended up in the hands of a man named James Perry, who, in 1993, was hired by a man named Lawrence Horn to kill his ex-wife, son, and son’s nurse. Horn hired Perry to kill his family so that he could inherit money from his quadriplegic son’s medical trust fund. Despite the fact that Perry followed twenty-seven of the book’s instructions, police pegged Horn as a suspect and traced the triple murder back to Horn and Perry through phone taps and financial records.

Mildred “Millie” Horn’s sister, Vivian Rice, filed a lawsuit against Paladin Press for incitement to murder. Paladin Press defended its publication under the First Amendment, but a Fourth Circuit judge ruled in Rice’s favor in 1997, claiming that Paladin’s publication of the manual did constitute incitement. The 700 remaining hard copies of Hit Man that Paladin Press had at the time were destroyed, but other copies already in circulation are available for purchase on Amazon and eBay. Additionally, PDF copies are widely available for free on the internet. Cases like Rice v. Paladin raise difficult questions about intent and effect, media ethics, and agency.

- Does this text encourage or facilitate murder?

- Who should be held responsible for the murder: the author? the publisher? the person who hired the hitman? the hitman? some combination?

- What constitutes incitement?

- Who gets to decide? By which criteria?

- What constitutes appropriate punishment for incitement?

Brad Serber

Postdoctoral Scholar

Assistant Director, Intercollege Minor in Civic and Community Engagement

Everywhere You Go, It’s There

Associate Professor

Director, Intercollege Minor in Civic and Community Engagement

Depts. of Communication Arts and Sciences and English

Three provocations:

Apple moved to break tech companies’ longstanding agreement with Unicode and to replace

its pistol emoji, which was an image of a six-shooter, with a squirt gun,

with the potential result that “a squirt gun sent from an iPhone will turn

into a handgun when received by an Android device, and vice versa…. In the

United States, this confuses taking a particular position on the Second

Amendment, concerning the right to bear arms, with the First Amendment,

which guarantees freedom of speech, including speech about arms.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/16/opinion/get-out-of-gun-control-apple.html

Although the National Rifle Association continues to pressure Congress to

withhold funding for research on gun violence, gun violence is a public

health issue. After the June 2016 shootings at Pulse nightclub in Orlando,

that research ban once again came under question.

http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-gun-research-funding-20160614-snap-story.html

Finally, a law that allows concealed carry of guns in campus buildings at

public universities in Texas went into effect at the beginning of this

month, prompting many faculty and students there to wonder about the new

law’s potential effect on free speech on campus. And the law took effect on

the 50th anniversary of the first campus mass murder in the United States.

http://chronicle.com/article/Texas-Picked-an-Ominous-Date/237264